In any organization, users will end up creating their own tools, outside of the official engineering process. This is a good thing, as these ‘citizen developers’ are often closer to the work and are addressing a need that they can see better than upper management, but the lack of any structure can create a lot of issues for the business. I’ve been on both sides of this discussion a few times in my career so I thought I’d write up my thoughts on how this can work.

In the grand tradition of recipe blogs, I’m going to start this article with a story that I find particularly relevant.

The spread of RSS on MSDN #

Back in 2005, RSS feeds were all the rage. People used them to get content updates from tiny blogs and massive news sites. MSDN (the Microsoft Developer Network), where I was an author and a member of the development team, had a few “official” feeds for top-level categories like “VB” or “SQL Server”, but there were hundreds of additional feeds for more specific topics like “Windows Server Deployment”, posted on the overview page for a specific sub-topic.

As more teams created these feeds and they became popular, we started to get bug reports about broken RSS. As a dev who has done a lot of coding on RSS and worked on the system that created our top-level feeds, the team would usually assign these bugs to me. As I dug into them, I found out that the authors were handwriting all these RSS files (which are just XML) in Notepad and publishing them manually. Hundreds of people hand editing XML each week to add and remove links was bound to have a high error rate, even with a group of technical writers, and malformed XML was common. I pointed out the errors, shared a link to an RSS feed validator, and assigned the bugs to the authors.

The engineering team had a few discussions about adapting the official system, which was based on product metadata, to support the very granular and custom-made categorizations that these feeds needed. Engineering’s capacity was full of higher priority work for quite a long way out, so this couldn’t happen anytime soon. I was in complete agreement with this decision, as doing this right would involve adding new types of metadata and some sort of feed designer. This would be a huge project in the MSDN system of the time, which was a mix of databases, Microsoft Word based authoring and file publishing through an FTP-like push system. We let the authors know that no solution was coming, and everyone seemed to find that reasonable and the discussion ended there.

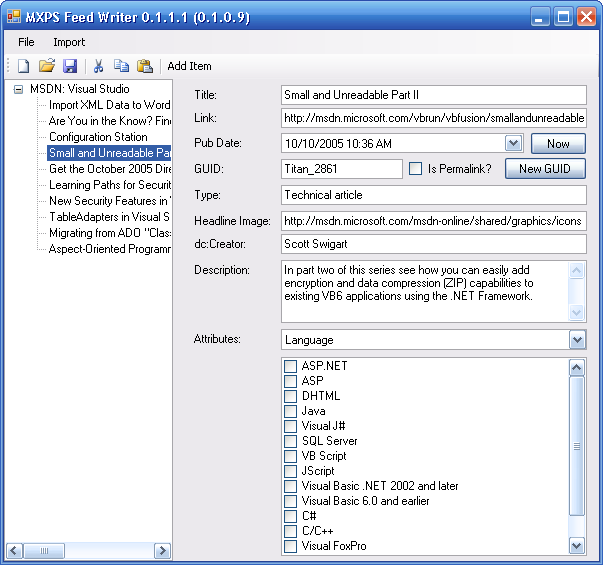

Jump forward a few days to the weekend, it was Sunday and one of my kids had fallen asleep on me, “trapping” me on the couch with my laptop. I had an idea that could help these authors and would also make a fun article and code sample to post online. I created a simple Windows Forms app that provided a rich editor experience over RSS files. You opened an existing file, or created a new empty one, then you added/edited/removed items like any line-of-business data editing application.

With very restrictive data entry, the app produced valid RSS and made the weekly update much easier. I sent it out to an author so they could test it, explaining that it was just a replacement for a text editor, and the rest of their workflow would be unchanged. I wrote a quick post about this a few days later, but I didn’t think too much about it, I had helped out some folks and hopefully reduced the # of invalid XML related bugs our users would run into. The author used the app for their weekly updates, loved it and started sharing it around with other teams.

No good deed #

After some time, someone in the content world wrote a nice email to my great-grand-boss (the head of MSDN engineering) along with their PM counterpart, praising this tool and how many hours it was saving their team.

This is where things started to go a bit sideways.

The PM lead was confused, why did we release a tool that wasn’t on the roadmap when we all agreed we couldn’t take on this RSS problem right now? I don’t know exactly what happened after that, but within days I was called to a meeting with all the top folks and everyone in between in my management chain. The various leads had decided that building this tool, outside of the official process, was unacceptable. All the authors were sent an email telling them to uninstall the app and to go back to using a text editor. Management explained to me that an unplanned app like this could create future issues, technical debt, etc. I argued about the relative simplicity and negligible risk of the app with no success.

Eventually management raised an issue that they saw as a bigger issue than the app itself. By working on this item, that we all agreed earlier was a low-priority, I was ignoring more important work. I was excited for a moment, here was the root of the issue and it was simply a bit of confusion that I could clear up easily. I explained that I had built this on the weekend, so it wasn’t instead of other work, I wasn’t ignoring the priority list and so there was no need to worry. The engineering and PM leads didn’t think this changed anything, if I was going to code on the weekend, I should be working on the next item in my queue.

I left that meeting a bit unsure of all of this, but not wanting to cause trouble, I took down an article with the RSS tool code and removed the link to download the tool itself. I decided that I would still do my normal technical blogging, but I would carefully avoid work-related topics in the future.

Some days later, my boss emailed me to let me know there had been more discussion about this. The PM lead had gone through my blog and saw that I had been writing sample code, little apps, and articles about coding for years. None of it was related to work, unlike the RSS tool, but it still concerned them. If I had time in my off-hours to code, I should be working on MSDN items. My boss said I was no longer allowed to write about technical topics, but I didn’t have to take down all my old posts.

It shouldn’t matter, but I would like to point out that I was not at all behind in my day job, in fact I was one of the more productive devs on the team. I’m not saying it would make it acceptable, but I would have found this reaction to my writing more understandable if I was having trouble hitting my deadlines at work.

I could have pushed back on this decision, and I’m not sure what would have happened if I had ignored the ’no coding outside of work’ rule, but I wasn’t confident enough to try it. So, I left the team at the first opportunity and moved to Channel 9, where my new boss was quick to reassure me that it was not only ok for me to blog and code in the public space, but it was awesome.

The tables are turned #

Flash forward 15 years, I am an engineering manager, and folks are discussing how we should handle ‘unofficial’ tools and development by people outside of the engineering team. My hypocrisy-level was high as I went through an initial set of feelings, including “don’t these people have their own work to do?”. Luckily, I kept most of those reactions to myself.

People create internal tools, especially unofficial ones, because they see a need. They want to make their job easier, make the team more effective, or produce better results. These are all virtuous goals, so we don’t want to stop this innovation. There are genuine issues and concerns with unofficial, unplanned, and unregulated software development though, so what we need is a way forward that enables this type of tool creation while minimizing the negative impact.

A way forward #

One of the reasons why it is hard to know how to handle ‘citizen development’ in your organization is that it covers a massive range of projects. No one objects to a useful Excel workbook to help people make budget plans, but what if that workbook grows to contain hundreds of macros and becomes the key to the budget planning system for the entire team? Before I left MSDN, I wrote up a proposal for how to decide if a project needed to go through the official software development process. It wasn’t well received, and I no longer have it around, but I think the idea still has merit. There are some general rules that apply to all tools and utilities, around setting expectations and keeping track of things, but how we handle things beyond that will depend on the tool’s role in the business, the risk it represents, and the impact it will have on the team that owns it.

Determining the level of concern #

My criteria when evaluating a tool/system is not some precise metric, but hits these main areas:

- What’s the business impact if this tool fails or is otherwise not available?

- Any security or privacy concerns.

- Sensitivity of data being handled.

- The ongoing impact on the team who creates or owns it.

Let’s walk through a few examples to see how this could work, starting with my original RSS tool.

The FeedWriter app #

The tool worked only locally, against a file that the user would still have to upload and publish through their regular process, which removes a lot of the concern about security and privacy. An author could have some information in there that was private, but they still had complete control over the actual publishing process. The tool couldn’t update the production site itself, for instance.

If the tool was broken or went away, the users would just go back to using Notepad or another editor, so the business impact would be low. The old process could be slower and more error prone, but it would be returning to a state that was previously determined to be acceptable. There could be an issue, after enough time, where users only know how to do this work using the tool and not manually, making it into a critical piece of the process.

In terms of ongoing impact to me, the creator of the app, it seemed like it would be low, as the scope of it was so constrained that it would be unlikely to have a lot of bugs. This could change though, if I kept adding features over time, which is not unusual.

There was one major issue with this app though, that I wouldn’t be willing to accept in my current role even though it didn’t occur to me at the time. Users installed my RSS tool from a link on my personal website, and it was setup to auto-update. Letting people inside the organization install software from an untrusted source, that updates without any oversight, is a big security risk. What if I left the company and decided to update the app to slip bits of profanity into the generated RSS files? Or someone was able to update the binaries up on my site to deliver a malicious payload to a bunch of internal Microsoft employee machines?

So, while this tool overall is minimal risk, it should at least be hosted internally, and its source stored in a place where our internal processes could see it. Expectations would also need to be carefully set that this was not official, even though someone from the dev team created it.

A TOC maker for a Microsoft Docs repo #

On Docs, we have the idea of table-of-contents (TOC) files, that contain a list of all the sub-topics in an area. Keeping this up to date with all the articles in a folder seems like a manual task that folks would appreciate some help with. A script that runs against your local copy of the repo and generates the TOC file? Similar in many regards to the RSS tool, it only works locally and doesn’t publish anything itself, making it a low-risk tool. If it breaks, you can always update the TOC file manually, so the business impact is low, and it seems simple enough that I doubt it would put much of a bug-fixing and maintenance burden on the creator. As above, my only concern would be keeping the source in a trusted location and not sending our authors out to some third-party site to get the script.

A new validation “Check” that runs in GitHub against new pull requests #

The Microsoft Docs system is based around Git repositories, so every content update is through a pull request. One terrific way to avoid publishing broken or low-quality content, is through automatic validation, GitHub runs checks as part of the PR process, and if the content fails one or more checks, publishing can be blocked. The engineering team has a few of these checks but imagine if an author decided to make a new one, ensuring that content always had their product name as .NET and not .net or .Net. Great idea as it helps avoid inconsistencies, and the team would love it.

Going through this list though, I would have a few concerns. What happens if this ‘check’ breaks and fails to run or returns incorrect results? Is publishing blocked because the check couldn’t pass? Since the check runs on pull requests, it can access content that isn’t published yet, which could include sensitive information. Are we confident it couldn’t accidentally leak that info? It needs some sort of access token or API key to work with our repository, is the creator storing and managing that authentication key safely (not checking it into the code, giving it only the minimal level of access needed)? If the creator leaves, can we update the app if needed or at least remove it from the repo to avoid blocking publishing?

A few more concerns that the previous two examples, so some oversight is needed, and the potential for blocking people’s work needs to be addressed.

A public API to let customers know about the latest content on Docs #

This goes all the way to our original RSS feature on MSDN, people like to be notified about updated or added content. It’s a common request, so what if a helpful person created a public API that scraped the site to determine when discover new items, and then published that API out to the world? The app is only dealing with public information, so no risk there, but our previous examples were tools for other employees to use and this is targeting customers. My level of concern goes up just because of that. If our customers are hitting this API, then it is a big deal if it is throwing errors or just stops updating. It is accessible on the public internet, so it is a security risk.

This would be a production app, and the organization would need to treat it like one.

An app that generates content and publishes it automatically #

Similar to the RSS tool, the TOC utility, and the even the API discussed above, what if we decide to have a page listing all the recently updated content on a part of our site? If we built this as a utility that scanned your local files, figured out what was new and spit out a text file, that would be handy and minimal risk. All the regular publishing workflow would apply, an author would look at the list and put it into a new markdown file, and someone would have to approve it before publishing. It’s always tempting to get rid of time-wasting manual steps though, so what if the tool went right ahead and updated the file using a pull request against GitHub? Not bad, still needs approval, so I wouldn’t be too concerned. That pull request though, that could get in way of keeping this file up to date, so why not simplify things by an automatic approval?

Every little step described above raises the level of risk, so even though the goal is the same, the level of concern could be widely different.

Setting the minimum bar #

While only a few applications may be of high concern, there are some minimum standards we could set for any tool. If there is at least some negative impact if it stops working, then leaving them completely unmanaged would be a mistake.

As a baseline, I would suggest we track these applications, even if it is through some mutually agreed upon location like a list on a Wiki page or a SharePoint site. In that list, we could describe the app, give links/instructions to access it, and contact information if there is an issue. If there is source code involved, that source code should be in a company owned location, where it would be possible for someone to take it over if the original owner left the company or team. The same goes for hosting, even in the case of a Power BI dashboard or a OneNote file, putting it into the shared team location means that access can be controlled centrally as needed. If there are cloud resources involved, they should be in a team/company subscription, not a personal one. Finally, there should be some level of documentation, even if it just explains what the tool does, where the code is, and how to file an issue or contribute an update. I would not recommend hosting the code, documentation, or resources for these tools alongside the work of the engineering team though. If the source is in the same Azure DevOps instance as the engineering team’s work, there could be an assumption that they are ready and able to support this app if needed.

Messaging and setting expectations #

To make any of this work, so that people can do this type of development, and it doesn’t result in chaos or a ton of unplanned issues, it is key to set the proper expectations. What level of support is the app creator promising, if any? If we have a link to “report an issue”, that implies someone is going to react to that issue. If the tool goes down, will someone work on getting it back up immediately, that day, or within a few weeks?

The organization needs to be clear about their position on this type of work. Is it allowed or even encouraged? Is it ok if it takes someone away from their ‘day job’? Do you need to ask first before rolling out a new project or only if it meets certain criteria? If the org does decide to encourage these projects, is there at least a need to document the tool or inform someone that you are building it? If an organization decided to completely forbid this type of work, it will still happen, but just more quietly.

As a tool creator, you need to be clear about what you are building, who it is for, and what your commitment level is. Are you open to feature requests? Do you have tons of time to spend on this or is it just something you built for yourself and people need to take it ‘as is’? Are you open to other people contributing?

Finally, the organization and the creators, need to set the right expectations with all the users. If it’s an unofficial tool, is it ok to use it? Should they be afraid that it is unsupported or that they could get in trouble for using it?

Moving from unofficial to official #

When a ‘citizen developed’ app becomes widely adopted and mission critical to the organization, it may ‘graduate’ to an official app. At this point, the business will expect the engineering team to take it on like any other project. This is a common, and almost inevitable situation, and one of the reasons why the engineers may react negatively to these side projects. If you knew that any random app, developed outside of your existing architecture by someone who doesn’t necessarily build production systems, could become your problem then you’d be a bit grumpy about them too. Taking on another person or team’s project is a complicated topic, and deserves its own article at some point, but the short answer is that it should not be done lightly. You should create a plan, shared with all parties, and allocate time to understand the tool and its current state. Next, document all the steps that are needed to bring this system into the engineering team’s world. This includes:

- Moving the code and any resources.

- Adjust permissions to control who can update and release it.

- Create or move a CI/CD workflow.

- Create, move, or update the documentation.

The intent of all these steps is to make the tool’s new status clear to everyone, including the original author. Without that clarity, the system will be in a vague in-between state where the engineering team is treating it like a production system, but the original contributors and users are still acting like nothing has changed.

Finally, as early in this ‘graduation’ process as possible, ensure everyone understands how this new project will impact the team’s capacity. No tool is without ongoing cost, even if it was created by someone else, so taking this on will reduce the time the team has to work on other priorities.